Donated on March 16, 1901 by the Governor-General of Canada, Sir Gilbert John Murray Kynynmond Elliot, 4th Earl of Minto, the Minto Cup was awarded to the senior amateur lacrosse champions of Canada. Lord and Lady Minto enjoyed such outdoor recreation and activities as ice skating and bicycling during their stay in Canada – and, apparently, in the summer months, Lord Minto also liked to play lacrosse.

Originally restricted to amateurs, within three years the first under-the-table professional teams were already competing for it. After 1904, with efforts to keep the professionals out of competition proving to be futile, it was made open to all challengers.

The Ottawa Capitals were handed the cup in 1901 as its first holders on account of being champions of the National Lacrosse Union the previous season. The first Minto Cup championship game was played on September 29, 1901 between Ottawa Capitals and Cornwall Colts. Won by Ottawa 3 goals to 2, the future King George V and Queen Mary were both in attendance as spectators – and after the match, he was presented with a lacrosse stick and the game ball.

Montréal Shamrocks won the league play for the National Lacrosse Union in 1901 and took over possession of the silver trophy. Later that year, the Shamrocks defeated Vancouver YMCA 5-0 in the first challenge from the Pacific Coast.

The Shamrocks became the first Minto Cup dynasty team as they managed to retain their hold over the trophy for six of the next seven seasons between 1901 and 1907 through a combination of winning league play in the National Lacrosse Union and fending off challenge attempts from outsiders.

In 1902, the Shamrocks defeated New Westminster in a two-game, total-goals series by an aggregate of 11-3. Montréal then repeated in 1903, 1904, and 1905 as league champions – but did not face another challenge from outside the National Lacrosse Union until they defeated the St. Catharines Athletics, champions of the Canadian Lacrosse Association, 13-4 in a two-game, total-goals series in 1905.

Next up was a challenge from Manitoba when a team from the small prairie town of Souris, located 23 kilometres southwest of Brandon, made a play for the cup, losing 10-2 in the first game and then throwing in the towel when the second game was subsequently cancelled.

Ottawa Capitals regained the cup in 1906. After the National Lacrosse Union finished in a four-way tie between Toronto Tecumsehs, Toronto Lacrosse Club, Ottawa Capitals, and Cornwall Colts each with 7 wins to their credit, a tiebreaker playoff series was required. The Tecumsehs defeated their crosstown Toronto rivals 12-7 in aggregate score while the Capitals defeated the Colts 8-2 in their two-game, total goals series. Ottawa then met the Toronto Tecumsehs in the two-game final and took the silverware on the heels of their lopsided 14-3 aggregate result in the two-game final.

Going against usual form, the Montréal Shamrocks collapsed in 1906 when they finished in last place. Goaltending was abysmal and the team suffered through many close losses, losing six games by a total of just eight goals. However the Irish would bounce back in 1907 and win the National Lacrosse Union with 10 wins from 12 games played for their sixth and ultimately final Minto Cup championship.

1908 was a pivotal year in the history of the Minto Cup when the New Westminster Salmonbellies defeated the Montréal Shamrocks 12 to 7 in their two-game, total-goals series. The first game of the series was a close 6-5 result before the Salmonbellies responded with a commanding 6-2 win in the rematch to clinch the silverware.

With the benefit of hindsight, the 1908 New Westminster-Montréal series signaled a changing of the guard and is probably the most historically significant event in the cup’s history until the juniors took over control of the mug. It saw the game’s first dynasty coming to an end with a brand-new one at the opposite end of the country ready to take its place. The victory for the Royal City was notable for two other important reasons: the New Westminster Salmonbellies were the last bonafide amateur team to challenge and win the professional trophy as well as the first club from the Pacific Coast to pry the silver mug from the hands of the Easterners.

The trophy then traveled out west on the Canadian Pacific Railroad with the Salmonbellies players and management – where it would remain entrenched on the Pacific Coast for the next 30 years. In the autumn of that year, New Westminster defended its new championship by winning all three games in a three-game, total-goals series 24-16 against the visiting Ottawa Capitals.

In defeating the professionals of the East, the amateur status of the Salmonbellies was now permanently tainted and revoked, like some irreversible mark of Cain staining both the team and its players forever. Because of this amateur vs. pro status conflict, a very serious and contentious issue in early twentieth-century athletics, the win by New Westminster also helped lay the groundwork for the start of professional lacrosse in British Columbia in 1909 when the British Columbia Amateur Lacrosse Association dropped the “Amateur” from its name and transformed into a professional organisation – albeit a league consisting of just two teams.

Once the professionals had firmly secured their control over the Minto Cup, a new gold trophy called the Mann Cup was then donated in 1910 as a replacement trophy for the senior amateurs to battle over. Until the death of the professional game, the Minto Cup was regarded as the more senior and prestigious trophy – with the Mann Cup taking over that position and honour in the mid-1920s.

Saskatchewan then made a run for the Minto Cup when the Regina Capitals splashed the cash and loaded up heavy on some serious Eastern talent in their bid for the cup. However even with such legends of the game as Alban ‘Bun’ Clark, Johnny Howard, Édouard ‘Newsy’ Lalonde, Art Warwick, Harry ‘Sport’ Murton, Angus ‘Bones’ Allen, and Tommy Gorman on their roster, the Capitals were still no match for the Salmonbellies. Regina lost the first game 6-4 before getting trounced 12-2 in the second game of the series.

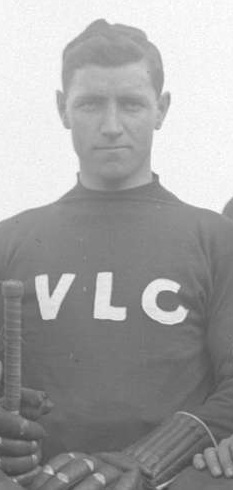

While the challenge may not have hit paydirt for the Regina Capitals, it did pay off well for some of their players’ wallets as Clark, Howard, Lalonde, and Allen were then picked up by Con Jones for his Vancouver Lacrosse Club. Eventually Clark and Howard would move on and join up with the rival Salmonbellies, but all four of these household names would nevertheless become fixtures in the Coast game.

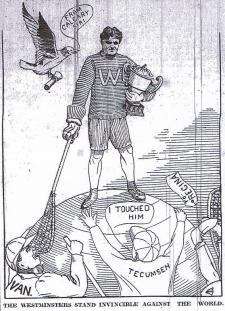

New Westminster Salmonbellies would face three more challenges from Ontario during the next two years, taking down the Toronto Tecumsehs, Montréal Amateur Athletic Association, and Montréal Nationals all in succession without conceding a single loss in the six matches played. Neither of the Montréal teams offered much of a challenge but Toronto Tecumsehs kept the Salmonbellies honest by playing to within 4 goals of taking home the silver mug. This period saw the height of New Westminster dominance on the field, and in a poll of Canadian sports writers carried out in 1951, they voted the 1909 and 1910 New Westminster Salmonbellies team the second greatest team in history. The Montréal Shamrocks who preceded them took the top-spot honours as the greatest team.

When New Westminster finally did lose the cup, it was to their rivals in Vancouver in 1911. In the greatest season ever seen on the Pacific Coast, New Westminster and Vancouver finished tied in league play with 5 wins apiece. A two-game, total-goals playoff series was then required to break the tie and determine who claimed the Minto Cup. It was finally Vancouver’s year to be crowned Minto Cup champions as they downed the Salmonbellies 4-3 and then 6-2 to lay their hands on the cherished trophy for the first time. Vancouver Lacrosse Club then successfully defeated another challenge attempt by the Toronto Tecumsehs, winning their first game 5-0 but dropping the second match 3-2 to the ‘Indians’.

New Westminster regained the Minto Cup in 1912 after defeating the Vancouver Lacrosse Club in league play. Later that same season, in what would prove to be the last East-West series for the Minto Cup until the junior game, New Westminster Salmonbellies defeated Cornwall Colts handily in their two-game, total-goals series by an aggregate score of 31-13. It was the last national series played by the professionals and it would be another quarter-century before Ontario would compete for the trophy again.

The last challenge series came the following year when the New Westminster Salmonbellies faced the Mann Cup champions, the Vancouver Athletic Club, in a two-game, total-goals series for the trophy. The Athletics had won the Mann Cup back in 1911 and now wanted a new challenge by making the jump to the professional game. It would be the only time in Canadian lacrosse history when the Mann Cup champions faced the Minto Cup champions head-to-head – with the silverware, in this instance, on the line. Despite being the national senior champions, the Athletics were no match for the seasoned professionals and lost their first game 9-1. The second leg saw a closer result but still not enough for Vancouver to dig themselves out of the hole. New Westminster retained the cup when they took the series 14 goals to 4.

From this point onwards, competition for the Minto Cup remained entrenched in British Columbia between New Westminster Salmonbellies and the Vancouver professional teams.

The First World War put a temporary hold over lacrosse in British Columbia for the duration of the war, as playing sports was viewed by many to be unpatriotic when one’s activities were better served focused on the war effort. By the time the professional game was revived in British Columbia, it was on its last, dying legs in Ontario. The teams there had neither the will nor the means to challenge for the Minto Cup.

In 1918 there was controversy surrounding the awarding of the cup. The Mainland Lacrosse Association had been formed that year with New Westminster and Vancouver as a pro league replacement to the then-inactive British Columbia Lacrosse Association. However a year later at the BCLA Annual Meetings held on May 8 and 15, 1919, the Minto Cup Trustees and British Columbia Lacrosse Association refused to recognise the results of the Mainland Lacrosse Association series as being official. Vancouver had won the eight-game series but would not be awarded the Minto Cup.

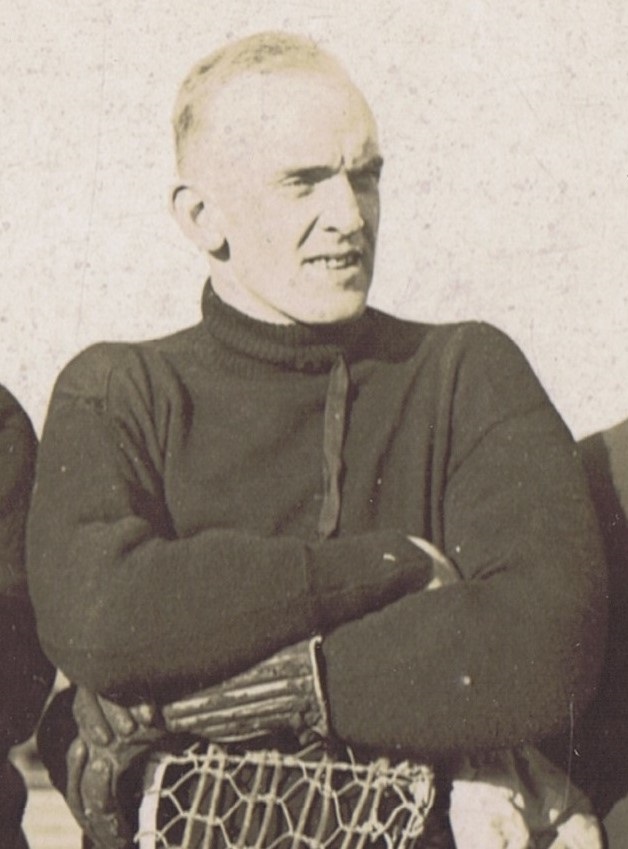

Vancouver claimed that they were in perfect order to organise a new league in lieu of the BCLA, which had suspended operations for the duration of World War One. New Westminster disagreed and claimed surreptitiously, somewhat well after the fact, that their club did not actually operate in 1918 despite the obvious. Out of disgust with the situation with New Westminster, Con Jones walked away from the pro game and turned his attention to supporting the amateurs. This was not the first time Jones had disagreements with the Salmonbellies and vice versa – and it wouldn’t be the last time either.

The professional game died in Eastern Canada on July 3, 1920; its demise in the East coming as no surprise for most observers of the game. For the remainder of the Minto Cup’s days as a professional trophy, league play in the British Columbia Lacrosse Association would determine the national champion. New Westminster Salmonbellies would dominate with five cup titles between 1919 and 1924 – with the Vancouver Terminals taking the trophy in 1920 in what was somewhat of an upset series, winning the three-game playoff series which was played even though New Westminster had won league play that year.

The last bastion of the professionals finally gave way when the game died more suddenly on the Pacific Coast, on June 2, 1924, when Con Jones once again walked away from the game, due to health issues.

This time, however, his departure was final – and the Minto Cup then went into cold storage as there were now no teams remaining in Canada, apart from the New Westminster professionals, who could now challenge and compete for it.

Or, rather, there were no amateur players nor amateur teams willing to issue a challenge for the trophy and be subsequently branded as professionals for the rest of their lives with no future opposition to play against. Any challenge made at this point would have been a one-way departure ticket from playing any further lacrosse, and other amateur sports that players were also involved in.

In 1929, there was some talk of offering it up for international competition. Cup trustee Charles A. ‘Charlie’ Welsh made an offer to the Canadian Lacrosse Association to turn the trophy over to them so it could be placed back into competition – this time as the world championship trophy. The plan never came to fruition, and instead the Lally Trophy would be inaugurated in 1931 for the amateur world champions, in the hopes the new trophy could somehow spark interest in the international game.

Finally, after twelve years of inactivity, the Canadian Lacrosse Association decided to revive competition for the Minto Cup – this time to be awarded to the national junior champions of Canada, starting in 1937. However, before the juniors were able to get their hands on the silver mug, one last chapter of drama was still left to play out: the trophy went missing when Charlie Welsh, the last remaining cup trustee, passed away suddenly on February 25, 1938.

While the Canadian Lacrosse Association had decreed the trophy for the national junior champion of Canada, at the time they actually did not have the legal authority to award the cup.

That was Charlie Welsh’s job as cup trustee, but he died before he would be able to officially rule that the Mimico Mountaineers were entitled to the silver mug when they won the series in 1938. Orillia Terriers had won the national championship the year before but had never actually been presented the cup except in name only. In December 1937, the Terriers received medals from the Canadian Lacrosse Association for their OLA junior championship, as the trophy was still residing out west in New Westminster with Welsh. Delivery of the Minto Cup had been promised for Orillia’s opening game of the 1938 season, but that never happened due to Welsh’s death.

Welsh’s successor, his wife, would have had the power to turn the cup over to the Canadian Lacrosse Association – if she hadn’t passed away herself just an hour after her husband. So a letter was drafted up and mailed off to Lord Minto in Scotland, the son of the original Lord Minto who had donated the cup, to ask him if he would deed the trophy over to the authority of the Canadian Lacrosse Association.

While the legal aspects were sorted out, another, more critical problem cropped up: where exactly was the cup? Charlie Welsh had never bothered to tell anyone where he had stored it. After a search lasting seven months it was eventually found, hidden away under a desk in his harbour commission office in the first week of October 1938.

However the legalities surrounding the grand old silver would not be settled until August 10, 1939. During an informal dinner held by the Canadian Lacrosse Association, the trophy deed was finally handed over in person by T.R. Selkirk, the estate administrator for Charlie Welsh, to J.A. McConaghy, president of the Canadian Lacrosse Association.

In August 1940, the cup was sent to Montréal for restoration work at a jewelry firm as the 39-year-old trophy began its new-found, second-wind with the junior game.

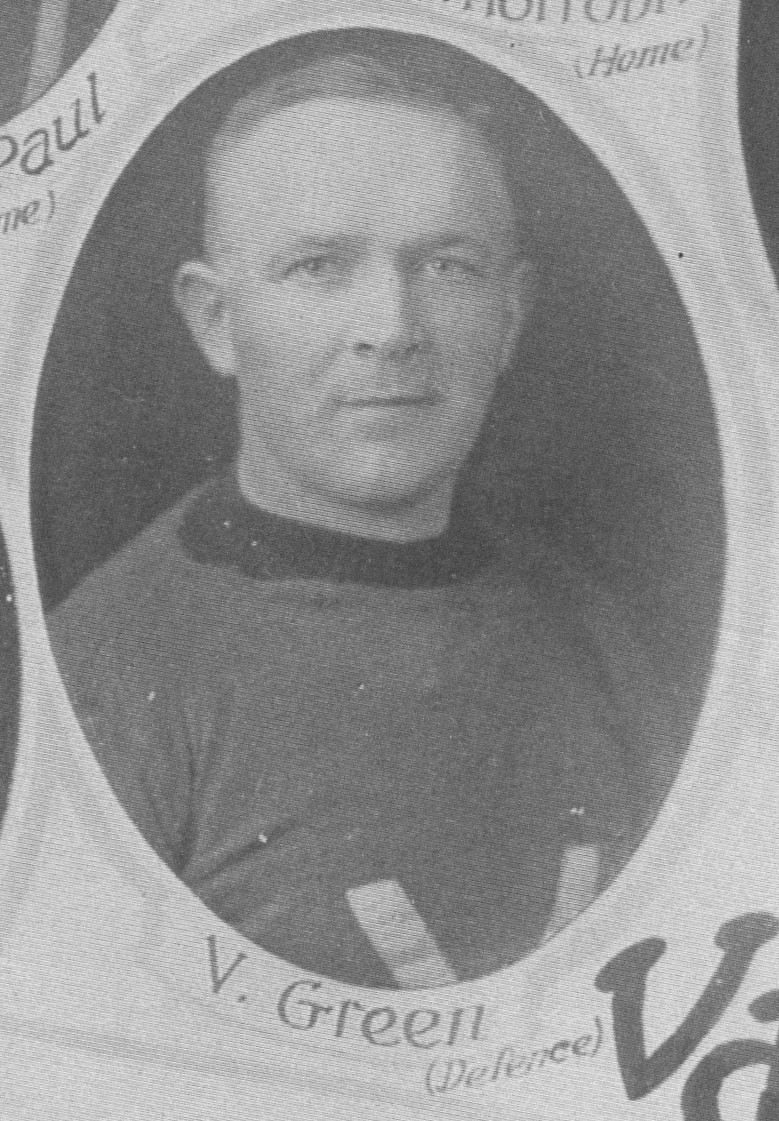

(PHOTO SOURCE: CLHFP006.60.1; stereoscope image courtesy of Todd Tobias collection; New Westminster Columbian 1921 and 1909; X979.115.1 author’s photo; CVA #99-41; photo by author)

You must be logged in to post a comment.